“They Are Welcome, But Will They Come Back for Good?”

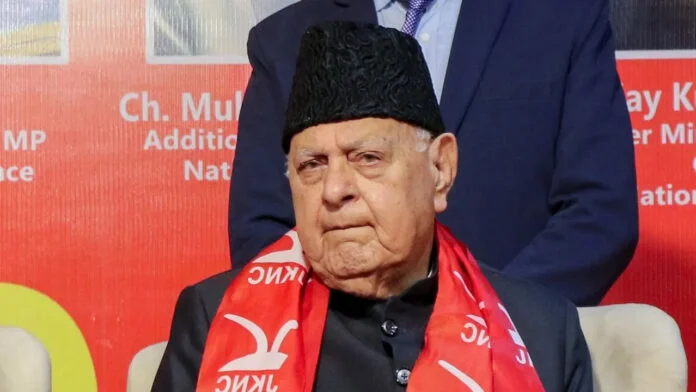

Farooq Abdullah on the Return of Kashmiri Pandits — Reality, Politics and the Road Ahead

By: Javid Amin | 19 January 2026

A Statement That Sparked Discussion Across the Valley and Beyond

On January 19, 2026, as Kashmir marked its 36th annual Exodus Day — the date many Kashmiri Pandits observe as the start of their forced displacement in 1990 — Farooq Abdullah, National Conference president and former Chief Minister of Jammu & Kashmir, made remarks that immediately drew widespread attention and sparked debate across political and social spectra.

Abdullah said that Kashmiri Pandits are always welcome to come back to the Valley, but added that he did not believe most of them would choose to resettle permanently, especially those of younger generations who have established lives, careers, and homes outside the region over the past three and a half decades.

“No one is stopping them from returning. Kashmir is their home,” he told reporters — but he struck a cautious, almost wistful note about the prospects of full, enduring resettlement.

In a region where the question of return and rehabilitation has been both an emotional and political flashpoint, Farooq’s comments touched on identity, memory, evolving demographic realities, inter-community relations, and the gap between symbolic welcome and practical action.

This feature unpacks the full context, political implications, historical background, community responses, and future possibilities around these statements — grounding every section in verified reports and expert insight.

Historical Background: The Pandit Exodus and Its Enduring Legacy

01. The 1990 Exodus — A Defining Event

The term “Exodus Day” refers to the mass departure of Kashmiri Pandits from the Kashmir Valley in January 1990, when threats, targeted killings, and intimidation by Pakistan-linked militants forced large portions of the community to flee for safety.

Before 1990, Kashmiri Pandits had been an integral part of Kashmir’s plural social fabric for centuries. Their departure — not voluntary migration, but a forced dislocation in the face of violence — left a lasting scar on the Valley’s demography, culture, and politics.

Estimates vary, but hundreds of thousands of Pandits left in the early 1990s, resettling mainly in Jammu, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, and other parts of India. Many moved more than once, and their communities grew around refugee camps and urban pockets. Some families lost property, many were dispossessed, and the trauma of displacement shaped generations.

02. Post-Exodus Government Approaches

Over the years, multiple governments — both regional and central — have expressed the intention to facilitate the return and rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits. Policies discussed have included:

-

Rehabilitation housing projects

-

Financial assistance to returnees

-

Security and employment guarantees

-

Community-specific development packages

However, critics argue that implementation has been inconsistent, with many plans never fully realised, altered, or discontinued due to political changes and security dynamics. Experts note that while the intent has surfaced periodically, the executive follow-through has often fallen short.

What Farooq Abdullah Said — And What It Really Means

On January 19, 2026, Farooq Abdullah’s remarks contained a mix of invitation, realism, and political parsing.

01. Welcome to Return — Symbolism of Belonging

Abdullah reiterated that nobody is preventing Kashmiri Pandits from returning to the Valley and that the region has a historical and emotional place for them as part of its composite culture.

“Who is stopping them? No one is preventing them. They should come back, as it is their home.”

This line echoes decades of political commitment from the National Conference to inclusive pluralism — that the Pandit community is part of Kashmir’s identity.

02. A Starkly Realistic Acknowledgement

Despite the warm welcome, Abdullah didn’t gloss over reality:

-

Most displaced Pandits have resettled elsewhere for decades

-

Children of Pandit families now have education, careers, marriages, and aspirations outside the Valley

-

Returning permanently would mean major life disruptions for those populations

Thus, his deeper point was pragmatic: expecting a mass, permanent return is unrealistic in 2026.

This is not a denial of right, but a recognition of contemporary demographic and socio-economic trajectories.

03. The “Visitor vs Resident” Distinction

Abdullah made a telling distinction: many Pandits will visit their homeland, reconnect with roots, attend cultural or family events, but not necessarily relocate back permanently.

“They may come like visitors, but I don’t think they will live here permanently.”

This subtly reframes the debate from one of physical relocation to emotional and symbolic connection.

The Political Context: Every Statement Is Political in Kashmir

Farooq Abdullah’s remarks cannot be understood in a vacuum. They were made against the backdrop of:

01. Exodus Day Protests and Demands

On the same day, Kashmiri Pandit organisations gathered in places like Jammu and the Jagti refugee camp, demanding not only the right to return but:

-

A safe, dignified rehabilitation policy

-

Parliamentary recognition of the 1990 exodus as genocide

-

A separate homeland within Kashmir through proposals like Panun Kashmir, a long-standing demand for a Pandit district or homeland within the Valley.

These demands remind policymakers that for many displaced families, return is not just an emotional desire but a demand for justice and identity restoration.

02. Political Backlash and Interpretations

Farooq’s comments also drew political reactions. Some leaders from other parties, including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), criticised his outlook as insensitive or dismissive of the community’s aspirations — framing it as a political abdication rather than a sober assessment.

Pandit groups even blocked the Jammu–Srinagar highway in protest, highlighting the depth of feeling in parts of the community.

Why Younger Generations Are Less Likely to Resettle

01. Social and Economic Roots Established Elsewhere

Decades of displacement mean that many Pandit families have:

-

Built professional careers

-

Secured stable education for children

-

Formed social networks and assets outside Kashmir

For many, the calculus of return is not purely emotional — it involves weighing livelihood, opportunity, and generational prospects.

02. Security Concerns Still Inform Decisions

Even though the security situation has improved compared to the early 1990s, historical memory and perceived risk continue to influence decisions. Pandit families who left during insurgency remember violence and threats, and those memories shape how safe permanent resettlement feels, even decades later.

03. Integration and Identity Over Time

Younger generations of Pandits have grown up in:

-

Urban centres outside Kashmir

-

Educational environments detached from Valley politics

-

Multicultural social spaces

Their identity, while tied emotionally to Kashmir, may practically be more associated with places like Delhi, Pune, or Bangalore.

This trend of identity evolution through migration is common among migrant communities globally.

Existing Pandit Presence in the Valley — An Important Fact

An often overlooked point in Farooq’s remarks, and confirmed by multiple reports, is that a significant number of Kashmiri Pandits never left the Valley in 1990 and continue to live in their ancestral localities peacefully.

These families stand as:

-

Living proof of coexistence

-

Cultural bridges between communities

-

A reminder that return need not be wholesale to be meaningful

Their presence is sometimes omitted in broader narratives that frame the Valley as uniformly devoid of Pandits — but the lived reality is more nuanced.

The Gap Between Symbolism and Policy

Farooq’s remarks expose a recurrent theme in Jammu and Kashmir politics:

01. Symbolic Welcomes Without Concrete Pathways

Many political leaders have expressed warm sentiments about Pandit return over the years. But there remains a policy gap between:

-

Welcoming words

and -

A robust, actionable rehabilitation framework

While gestures matter, actual policy involves:

-

Land allocation

-

Security guarantees

-

Housing and employment support

-

Sustained financial incentives

-

Community integration programmes

Without these, symbolic invitation may remain hollow.

02. Central vs Regional Responsibility

Abdullah hinted that the ultimate responsibility now lies with the Central Government — especially in areas like long-term rehabilitation and socioeconomic security — shifting some onus away from the UT government.

This is politically sensitive because the relationship between regional and central authorities on Kashmir policy is often fraught and complex.

Community Responses: Support, Critique, and Aspirations

01. Pandit Organisations and Youth Voices

Groups like Youth 4 Panun Kashmir and other Pandit representatives have been vocal — blocking highways, staging demonstrations, and pushing for legislative recognition of their exodus as a genocide.

Many demand:

-

Dedicated rehabilitation law

-

Special status for Pandit returnees

-

Security and integration guarantees

Their perspectives reflect not just nostalgia, but contemporary struggles for dignity and justice.

02. Divergence Within the Community

Not all Pandits hold the same view:

-

Some see return as essential

-

Others prioritise economic security

-

Some advocate an autonomous homeland concept

-

Others focus on reconciliation and coexistence

Understanding these varied voices is crucial for comprehending the larger debate.

Security, Trust and Inter-Community Relations

01. History of Hurt and Fear

The exodus was not merely relocation; it was triggered by violence, threats, and loss of life. This history has created deep emotional scars among older generations, which are passed down to younger ones.

02. Coexistence Realities in 2026

Today, parts of the Valley coexist peacefully, with communities living shoulder to shoulder. Abdullah’s own references to Pandits living in the Valley underscore this reality — however limited and localized it may be.

03. Political Exploitation vs Genuine Reconciliation

Another layer is the political dimension where some actors may exploit community grievances for electoral or ideological advantage — a pattern often observed in conflict-affected societies.

Balancing political rhetoric with genuine reconciliation remains a long-term challenge.

Policy Options and Long-Term Pathways

Experts in governance and conflict resolution suggest that lasting solutions may involve:

01. Phased Rehabilitation with Guarantees

A possible model would involve:

-

Phased, optional returns

-

Community-defined safe zones

-

Security liaison teams

-

Economic opportunity programmes

This respects choice while building infrastructure for those who wish to return.

02. Constitutional and Legal Protection Frameworks

Creating legal safeguards for minority communities, integrating them into local governance, and ensuring constitutional guarantees can make return more viable.

03. Dialogue Across Generations

A crucial step is inter-community dialogue that acknowledges history, trauma, and aspirations, not just for Pandits but for all Kashmiris.

Conclusion: Reality, Hope, and a Tough Road Ahead

Farooq Abdullah’s remarks on Kashmiri Pandits are layered:

-

A warm welcome couched in realism

-

A recognition of how displacement reshaped identities

-

A pointed acknowledgment that permanent resettlement cannot be assumed lightly

They do not close the door — but neither do they open it unconditionally.

The debate over Pandit return highlights the larger challenge in Jammu and Kashmir’s political landscape: reconciling history with present realities, blending symbolism with policy, and building a future where choice, dignity, security, and opportunity are available to all.

As Kashmir continues to evolve politically and socially, the conversation around Pandit return will remain central to how the region understands itself — past, present and future.