Farooq Abdullah Slams Centre Over Statehood Delay: J&K’s Fight for Dignity and Democracy

By: Javid Amin | 03 Sep 2025

A Region in Waiting

Jammu & Kashmir has always stood at the crossroads of India’s political debates, constitutional experiments, and democratic struggles. Once a state with special status, rich in history, culture, and identity, it was reduced to a Union Territory (UT) in August 2019 when the Union Government abrogated Article 370 and bifurcated the region into two UTs — Jammu & Kashmir, and Ladakh.

At the time, the Centre promised that the UT status for J&K was “temporary” and that statehood would be restored “at an appropriate time.” Six years later, that promise remains unfulfilled.

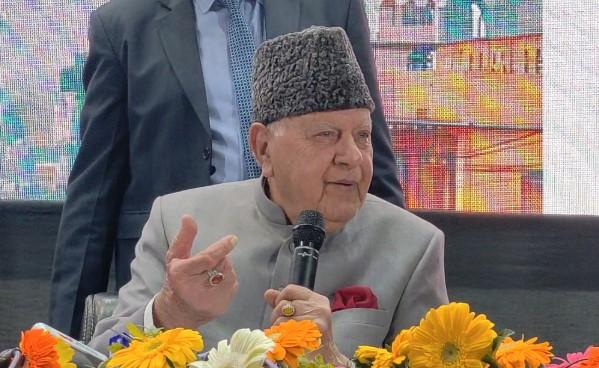

This prolonged delay has triggered anger, frustration, and disillusionment among the people of the Valley. One of the strongest voices against this delay has been that of Dr. Farooq Abdullah, former Chief Minister and veteran leader of the National Conference (NC). His recent remarks in Anantnag have reignited the debate over J&K’s political dignity, with his words echoing not just as political rhetoric but as a moral and constitutional indictment.

“This is not about politics,” Abdullah declared, “It’s about justice, equality, and dignity. One day, New Delhi will regret its decisions regarding J&K.”

His statements underscore the growing frustration in the region — not only among politicians but also among ordinary citizens who feel stripped of their democratic rights. This article explores Abdullah’s critique in depth, tracing the historical journey of J&K’s statehood, analyzing the constitutional dimensions, recording political reactions, and assessing what the delay means for democracy in India.

Farooq Abdullah’s Rebuke: Voice of Discontent

Dr. Abdullah, speaking to NC workers in Anantnag West, delivered a stinging rebuke to the Central Government. His speech was not laced with the usual political promises; instead, it was a moral appeal to restore dignity to a people who have lived through decades of broken assurances.

Key Highlights of His Remarks:

-

On Delhi’s approach to J&K: Abdullah criticized successive governments for pursuing a “security-centric” approach that has failed to win the confidence of the people. “You cannot rule hearts through force,” he said, “you can only rule them through justice.”

-

On democratic betrayal: He pointed to the high voter turnout in the 2024 Assembly elections, which was seen as a reaffirmation of people’s faith in democracy. Yet, the continued denial of statehood undermines that trust.

-

On dignity and equality: Abdullah reminded the Centre that reducing J&K to a UT was more than an administrative change; it was a downgrading of identity. “We have been placed on a lower pedestal,” he warned.

-

On future regrets: Perhaps his most striking line was his warning: “One day, New Delhi will regret its decisions regarding J&K.” This was less a threat and more a prediction that alienation, if left unaddressed, will carry long-term costs.

Abdullah’s words have found resonance beyond his party. Many civil society groups, academics, and even apolitical citizens view the statehood delay as a denial of constitutional justice.

Historical Journey of J&K’s Statehood

To fully grasp the weight of Abdullah’s criticism, one must understand the historical trajectory of Jammu & Kashmir’s political status.

1947–1950: Accession and Autonomy

-

In October 1947, J&K acceded to India under special conditions. The Instrument of Accession allowed New Delhi control only over defense, foreign affairs, and communications, while all other matters remained with the state.

-

Article 370 of the Indian Constitution enshrined this special status, granting J&K its own Constitution, flag, and autonomy over land laws and residency rights.

1953: The Sheikh Abdullah Dismissal

-

Sheikh Abdullah, Farooq’s father, was dismissed as Prime Minister of J&K in 1953 and jailed. This event is widely seen as the first breach of democratic trust between Delhi and Srinagar.

1965–1980s: Gradual Erosion

-

Constitutional provisions and presidential orders slowly chipped away at J&K’s autonomy. By the 1980s, most provisions of the Indian Constitution applied to J&K.

-

This period also saw frequent imposition of Governor’s Rule.

1990s: Militancy and Central Rule

-

The eruption of militancy in the 1990s brought prolonged Governor’s Rule.

-

Elections were often suspended, and when held, they were marred by low turnout and allegations of rigging.

2002–2018: Coalition Politics and Protocol Disputes

-

With relative peace returning, coalition governments (NC-Congress, PDP-Congress, PDP-BJP) attempted governance.

-

Yet, Centre-state tensions remained constant, with Chief Ministers often complaining about protocol disputes, bypassing of elected leaders, and excessive LG/Governor interference.

2019: Abrogation of Article 370 and Statehood Loss

-

On August 5, 2019, Article 370 was abrogated, and J&K was bifurcated into two UTs.

-

The move was projected as an integration measure, with assurances that statehood would return once “normalcy” was achieved.

-

Ladakh was carved out as a separate UT without legislature, while J&K retained a promise of eventual restoration of statehood.

Today, six years later, that promise remains unfulfilled.

Constitutional Perspective: Statehood and Federalism

Statehood in India is not merely a status symbol — it is a cornerstone of federalism.

What Statehood Means:

-

States enjoy full legislative powers, control over police, land, and governance.

-

Union Territories (UTs), however, are centrally administered. In the case of J&K, a Lieutenant Governor (LG) appointed by the Centre wields significant powers, often overshadowing the elected government.

Why This Matters for J&K:

-

J&K was a full-fledged state for decades, with a unique constitutional relationship. Downgrading it to a UT was unprecedented.

-

Article 1 of the Constitution recognizes India as a “Union of States.” Federalism, as upheld by the Supreme Court, is part of the basic structure doctrine.

-

Denying J&K statehood raises serious constitutional questions: Can a state be permanently downgraded? Is prolonged UT status compatible with India’s federal spirit?

Legal scholars argue that J&K’s prolonged UT status reflects “constitutional backsliding.”

The Democratic Deficit: Why Voters Feel Betrayed

The 2024 Assembly elections saw impressive voter turnout, especially in Kashmir, where people defied boycott calls to participate. Citizens saw elections as a chance to reclaim agency.

Yet, the denial of statehood after such participation feels like a betrayal.

-

People’s Mandate vs. Central Policy: Citizens voted in good faith, expecting that Delhi would honor its promise. Instead, power continues to rest with the LG.

-

Voices from the Ground: Civil society groups report growing disillusionment. “What is the use of voting,” asked a shopkeeper in Pulwama, “if Delhi will still decide everything?”

-

Alienation Risk: Denying statehood risks pushing mainstream voices aside, creating space for extremism.

In essence, the democratic deficit is widening.

Political Reactions and Party Lines

The delay in restoring statehood has sparked a range of political reactions:

-

National Conference (NC): Farooq and Omar Abdullah demand immediate restoration. NC frames it as a matter of dignity and constitutional justice.

-

People’s Democratic Party (PDP): Mehbooba Mufti and Iltija Mufti call it a “denial of democracy.”

-

Congress and Left: Demand federalism reforms, warning against “central overreach.”

-

BJP: Defends the delay, saying statehood will return at an “appropriate time” once security is stable.

-

Regional Parties (Apni Party, People’s Conference, AIP): Mixed reactions — some push for early statehood, others cooperate with Delhi.

Comparative Lens: Lessons from Other Regions

J&K’s situation is not isolated; other regions have had similar experiences.

-

Delhi: UT with legislature, but LG often dominates. Supreme Court has repeatedly intervened to balance powers.

-

Puducherry: Similar tussles between CM and LG.

-

Goa and Himachal Pradesh: Both were once UTs, later upgraded to states.

The comparison raises an uncomfortable question: If smaller territories like Goa and Himachal could achieve statehood, why is J&K — with its population, size, and history — still denied it?

Risks of Continued Delay

The costs of prolonging UT status are significant:

-

Erosion of trust in democracy.

-

Weakening of mainstream politics, allowing fringe or radical voices to rise.

-

Paradox of development vs. dignity: While infrastructure projects advance, people feel politically powerless.

-

International scrutiny: Reports by global organizations often cite J&K’s democratic deficit as evidence of India’s shrinking democratic space.

Possible Pathways Ahead

1. Full Restoration of Statehood:

-

Clear timeline, powers restored over police, land, and governance.

2. Partial Restoration (Delhi Model):

-

Assembly restored but with Centre controlling police and land.

3. Status Quo:

-

Continued UT status with no clear timeline — likely to deepen alienation.

Bottom-Line: A Call for Justice and Dignity

Farooq Abdullah’s remarks are more than political posturing; they are a cry for dignity. His warning that Delhi may one day “regret its decisions” reflects the dangers of alienating a people who have historically endured broken promises.

The restoration of statehood is not a concession. It is a constitutional necessity and a matter of democratic credibility.

India’s federal spirit, its global image as the world’s largest democracy, and the trust of millions in J&K are all tied to this single question: When will statehood return?

Until then, J&K remains a region in waiting — waiting for justice, equality, and dignity.